Portrait of the Artist

Fort Worth museum gives floor to world's greatest modern portrait artist

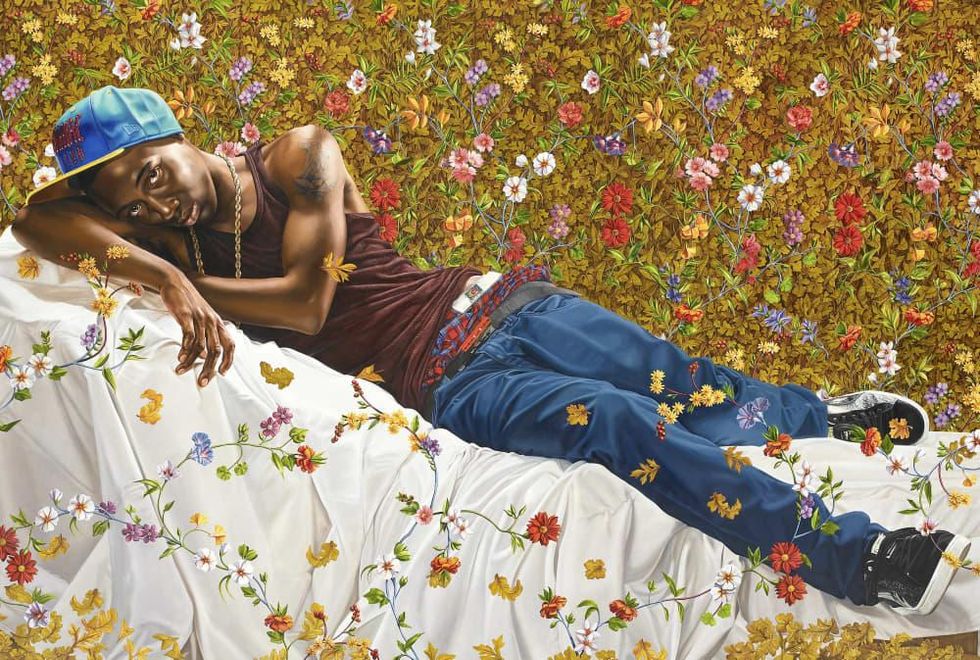

Larger than life or intimately detailed like religious saints, crafted of luminescent stained glass or sculpted in touchably textured bronze, the works of Kehinde Wiley transform their subjects into heroes and icons, modern royalty rather than the young, urban men and women they really are.

South Central-bred and Yale-educated, Wiley has become famous everywhere from blue chip museums to the set of Empire. His paintings, which borrow freely from the history of portraiture while remaining completely contemporary, have a populist appeal that belies his meticulous technique.

This is all evident in “A New Republic,” an overview of the artist’s prolific 14-year career running through January 10 at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth. Formerly staged at the Brooklyn Museum, this epic show is a rare opportunity for Texans to see almost 60 works in Wiley’s oeuvre, including his bronze busts and a chapel-like structure housing his new stained glass “paintings.”

Says exhibition curator Andrea Karnes, “Kehinde’s work is among the best within the genre of portraiture; it is formally exquisite. Conceptually, his work channels the past while it is also firmly planted in the present.

“His paintings, sculpture, and stained glass pieces point to omissions within the Western tradition of art, and Western history in general. His inclusion of people of color, and of women (who have also taken a backseat to men in the European masterworks Kehinde refers to in his contemporary imagery) makes his work provocative and lasting in the minds of viewers and the art world at large.”

When he was a child in South Central Los Angeles, Wiley’s mother was prescient enough to send him and his twin brother to art classes at the Huntington Library, a two-hour drive away. Hours spent walking through the magnificent halls and gardens, and a separate trip to Russia to paint in the forest outside St. Petersburg, shaped the young talent.

His early understanding of the trappings of social class and empire alluded to in great portraits — and the study of their technical mastery — led Wiley down the path of what eventually would become his own unique style of artistic expression.

In a chat at the Modern with Dr. Eugenie Tsai of the Brooklyn Museum, Wiley said, “My mother created this strange little garden for us to grow up in. We were economically impoverished, but we were enriched in ways you can’t imagine. She started this fire, and it got me looking at picture making. It got me looking at the seams where identity lies … the social injustices that undergird the reality of everyday life.”

After earning his BFA at the San Francisco Art Institute, Wiley garnered an MFA from Yale University. Moving to New York post-graduation for a residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem, he furthered his examination of “the type of black masculinity that was oftentimes misunderstood or couldn’t possibly be processed.” Casting men on the street for their peacocking fashion sense in the mid-2000s, he attempted to capture the ephemerality of fashion and pop culture in a timeless form.

Allowing his models to choose their favorite masterworks, he began a “strange back and forth” between subject and artist that remains to this day. These works share space on the Modern’s walls with pieces from his “World Stage” series, which was cast in countries such as Nigeria, Senegal, Sri Lanka, India, and Brazil, and from “Economy of Grace,” his first portraits of women outside of art school.

Patrons of the museum can further explore the influences behind Wiley’s unique viewpoint at the Modern ’Til Midnight: Beats and Baroque event October 24 and the museum’s “Culture, Class and Style” film series October 30 and 31.