Water lilies and more

Monet’s garden blooms with surprises in new Kimbell Art Museum exhibition

No one would have blamed a 73-year-old Claude Monet for wanting to putter in his garden instead of paint it. After all, cataracts were wearing down his eyesight, he was mourning the deaths of beloved family members, and hauling canvases in and out of his studio had become a physical challenge.

Yet in his twilight years, Monet (1840-1926) managed to produce some of the most iconic paintings in history at his garden at Giverny. More than 50 examples have gone on display in the blockbuster exhibition "Monet: The Late Years" at the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth.

The exhibition charts the evolution of Monet’s practice from 1913 to his death in 1926. For the Kimbell, it's a continuation of the biographical sketch started with their 2016-17 exhibition “Monet: The Early Years.”

Except it’s even more interesting. Because life makes people more interesting as they get older, and Monet was no exception.

"We're meeting an artist when he's in his 70s, when many artists would be overwhelmed by the challenges of his life," says the Kimbell's George T.M. Shackelford, the curator of the exhibition. "But Monet, with great energy and incredible joy, begins to embark on a new work that is bigger and more ambitious than almost anything he’s ever done. It’s a period in Monet's life of incredible dedication and real bravery."

Although the paintings in the exhibition all depict scenes from his garden — no beach scenes or self-portraits here — surprises abound in each gallery. "Surprise," in fact, is a word that Shackelford uses a lot in a walk-through of the show.

"I think the combination of dedication and bravery, ambition and joy that you will see in these works of art will be one that will surprise and delight you," he says.

A surprise at the start

The very layout is meant to enchant visitors from the beginning. In the first gallery are works painted before 1907 — namely, those sublime water lilies that everyone knows and loves.

"That is me trying to lull you into the mistaken apprehension that you’re already familiar with the show," Shackelford says slyly. "I want you to go in and feel like you’re in a nice, warm, cozy bath of a water lily pond and that everything is what you know already.

"Because I want you, when you turn the corner into the next gallery, to be surprised by the transformation that takes place in Monet’s art in the summer 1914.”

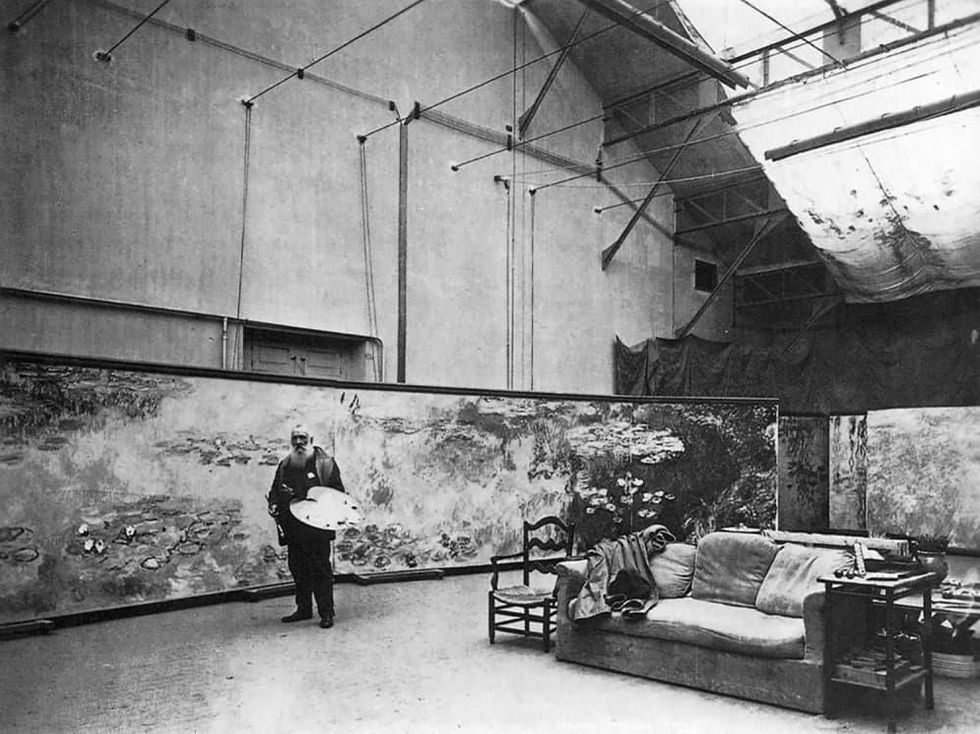

Suddenly, the canvases get big. Tall. Long. One of them is 6-foot-6; Monet was 5-foot-7.

Here's why: After the death of his beloved second wife, Alice, in 1911, a grieving Monet went on hiatus, which lasted through his oldest son's death in 1914. Then suddenly, he picked up his paintbrushes again.

"After a period of intense mourning, Monet in a way snaps out of it, and suddenly he is painting again with incredible enthusiasm and great joy — a kind of joy with a sense of being liberated from grief," Shackelford says.

And with this "reawakening" came an idea — a really big idea. He would paint scenes from Giverny on a grand scale, a project called Grandes Decorations, which would be installed in France's Orangerie of the Tulleries Gardens in 1927, after his death.

"Behind that line is an enormous number of paintings that were made as part of the process, and a lot of that is what we are showing you in this exhibition," the curator says.

Growing flowers and growing restless

Focus shifts from water lilies on the pond to the rest of the colorful riches in his garden — irises, daylilies, and agapanthus. Monet wasn't just a painter of gardens, he was a champion gardener himself.

"By the 1920s, Monet was also known in gardening circles for his cultivation of agapanthus and irises," Shackelford says.

Visitors are encouraged to get up close to the large paintings, to observe surfaces and brushstrokes and layers of paint this way and that; occasionally, spots of the white canvas peep through.

Monet was known to paint and repaint over and over and was never fully satisfied with his work in his later years, the curator says. "They looked like many other things before Monet got finished with them," he says. "Actually, he only finished with them when he died."

Going small again

But just as guests adjust to viewing the larger-than-life canvases that fill two galleries — surprise! — they shrink back to "normal."

In the final galleries are paintings of the garden's Japanese bridge, houses, and weeping willows. The Monet masterpiece that the Kimbell owns, Weeping Willow — the work that became the impetus for the whole show — appears in the final section. The fact that it was painted in 1918, toward the end of World War I, likely is no accident, Shackelford says.

"If you're painting in fall of 1918, you don't know the war is going to end in November," he says. "When Monet is painting weeping willows, he's thinking about mourning. The weeping willow, in France just as it is in many other cultures, is a symbol of mourning."

Many people from Monet's village had died, and Giverny was so close to Paris that he could hear the cannons and air raids bombing the city, he says. "Monet was not very far away from the sounds and the overwhelming visceral impact of the war going on at the same time," he says.

Last strokes of genius

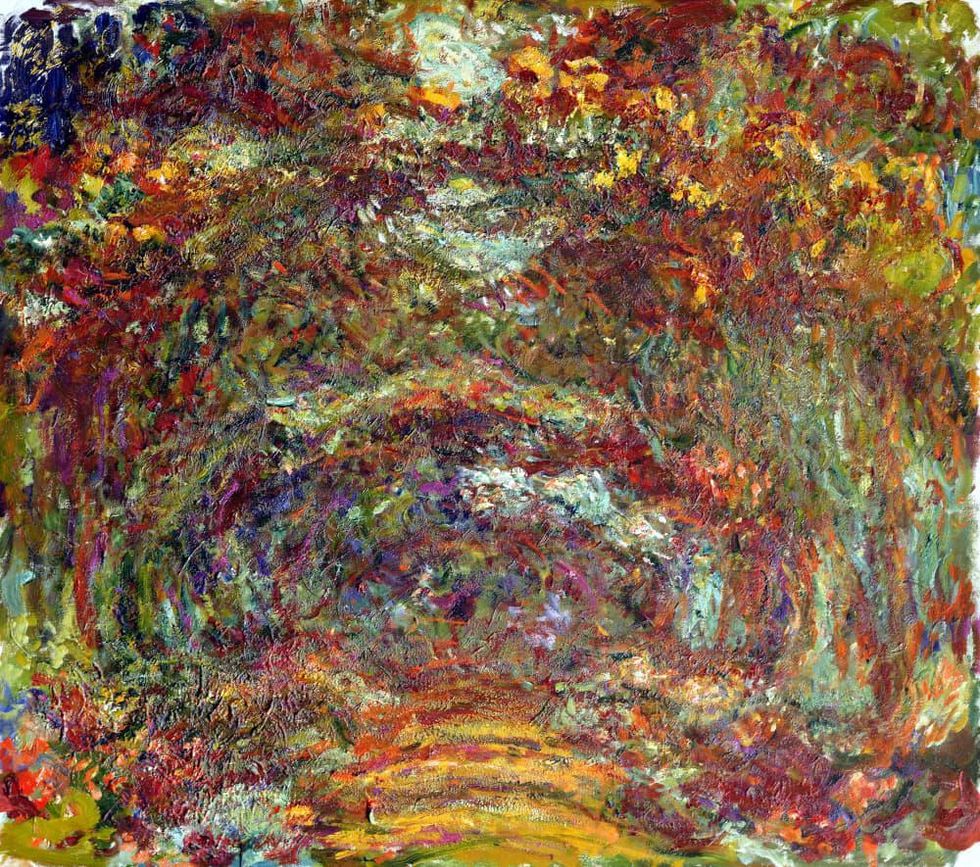

The paintings in the final galleries look markedly different from the serene water lilies shown at the beginning. They use darker, more saturated colors, with intense, powerful brushstrokes that result in pictures that almost look chaotic. Monet was seeing differently, and painting differently.

Despite undergoing three surgeries, the artist's cataracts had blurred his vision and shifted his perception of color. Only a genius, Shackelford said, could compensate the way that Monet did.

"Look at the individual brushstrokes and you'll often see two and sometimes three colors he's mixing on the brush," the curator says. "This man who isn't seeing very well is able to touch his paint in two different spots of paint on his palette. That is not something you can do if you're not in control."

"Even in the paintings that seem the most chaotic, there is a kind of brilliance that is the work of someone who fundamentally knows what he's doing, and he's willing to take risks."

According to the exhibition catalog, as he entered his 80s, Monet had become something of a giant even though his physical capabilities had diminished. He viewed his final works as a culmination of a lifetime of studying nature, and his attitude toward the natural world that gave his younger works their magic was still there.

"The final works are literally the last strokes of genius," Shackelford says, "of somebody who was capable of so much strength and bravery so late in his life."

---

"Monet: The Late Years" is on view through September 15 at the Kimbell Art Museum, 3333 Camp Bowie Blvd., Fort Worth. Admission is $18 for adults, $16 for seniors and students, $14 for ages 6-11, and free for children under age 6. Admission is half-price all day on Tuesdays and after 5 pm on Fridays. Visit the website for more information and tickets.