Worlds Apart

Artist's intricate universes get their due in 20-year survey in Fort Worth

With their cult member protagonists, hidden violence, and cataclysmic landscapes, the 60 works featured in "We, The Masses" may lead the viewer to assume artist Robyn O'Neil has a nihilistic view of the world.

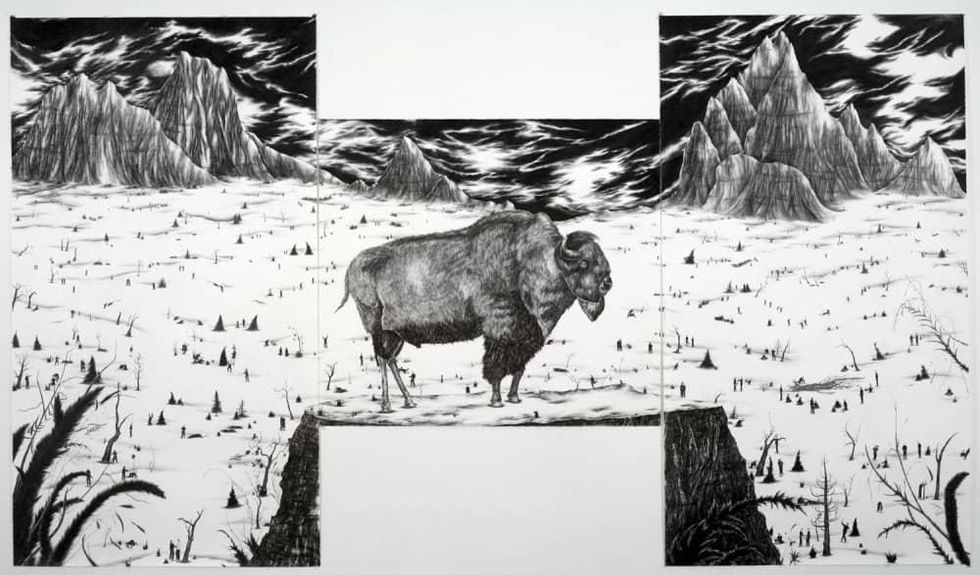

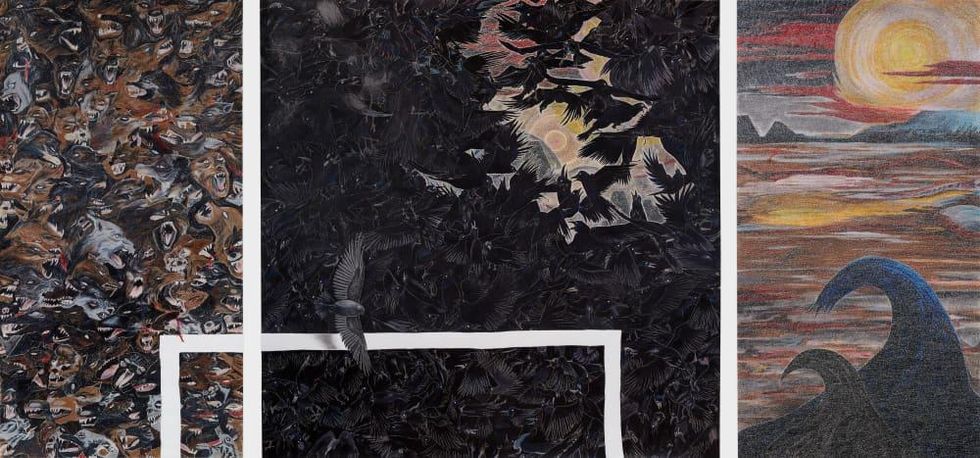

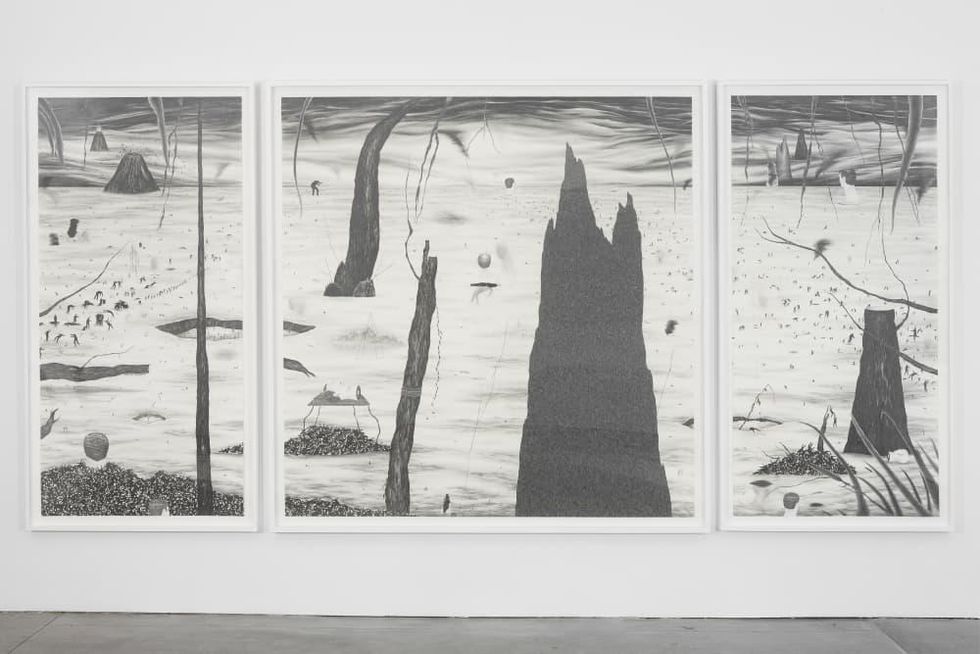

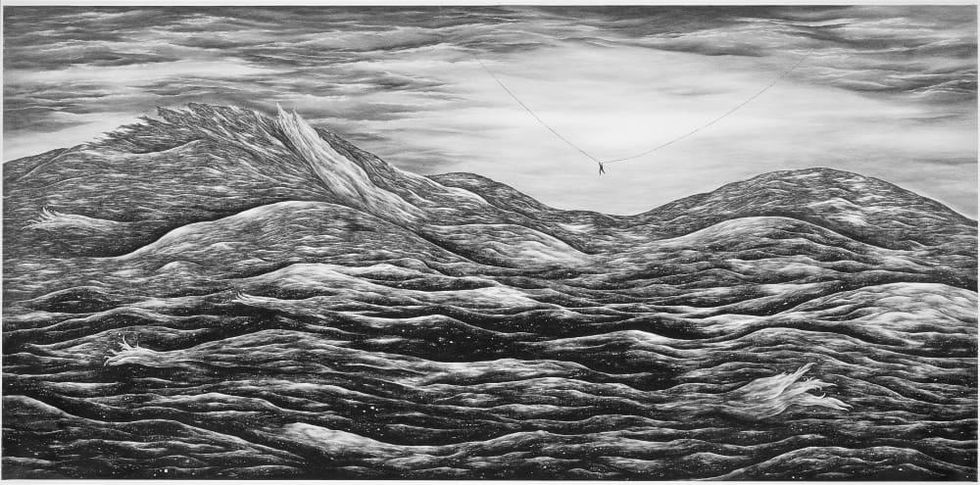

Seemingly embodying some kind of societal breakdown, pieces like As Ye the Sinister Creep and Feign, Those Who Once Held Become Those Now Slain and her three-years-in-the-making triptych Hell are filled with subjects fighting and embracing, vomiting and drowning. But O'Neil herself possesses a far more effervescent attitude, pouring any angst she might possess into her precise images patiently executed with a 0.5 mechanical pencil.

There's a lot to unpack in O'Neil's work. For the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth's associate curator Alison Hearst, who pulled "We, The Masses" together over the last year, it was fascination at first sight.

"I first saw Robyn's work when I was in graduate school around 2007 at Talley Dunn Gallery," Hearst says. "I thought it'd be great to do a smaller show that put art drawing into context, but after seeing (the newer works), I wanted to show her trajectory of the past 20 years."

Meticulous in her approach, from the crayon drawing she executed in kindergarten included in "Masses" to her more recent mash-ups of artistic homage and lowbrow ephemera, O'Neil's oeuvre has a little something for everyone who views it.

"From the early work in 2005 to the present, there are so many thematic threads that run throughout about the environment or the world we live in," says Hearst. "And her work is so accessible. It's visually interesting. (The pieces) with the figures are super relatable — we can all place ourselves in these scenarios. It's very serious, but there is humor in it."

The intricately drawn little men that populate a large part of the show first made their debut around the year 2000, at a time O'Neil was shifting from painting into her highly detailed drawings. Her father and his friends originally inspired the amusing middle-aged protagonists clad in the same black sweatsuits and Nike tennis shoes as the Heaven's Gate cult. But while attending graduate school at the University of Chicago, an unfortunate occurrence led O'Neil to give her characters more sinister fates.

Having befriended two "big Midwestern guys" who lived in her building, O'Neil was shocked to return home one day and find one of them had jumped off the rooftop of the apartment complex.

"It really, really traumatized me," O'Neil says. "From that moment on, I started to create tragedy around these guys and make the world lot more treacherous. Even if the drawings of the men were funny, the backgrounds weren't so funny. I said, 'These guys have nothing to do with my dad, I can multiply them and use them as humanity.'"

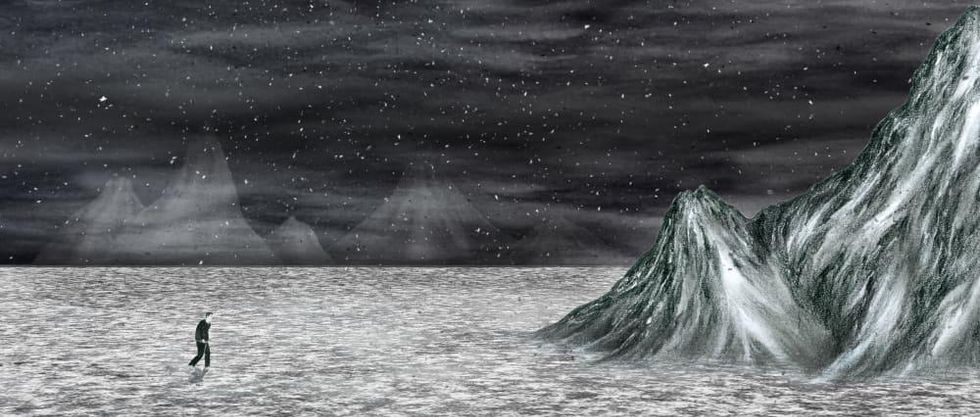

Having been raised in Nebraska and West Texas, O'Neil also gravitated to Mother Nature's more intemperate moods, stranding her heroes in snowy vistas or submerging them in turbulent waters. By the time she suspended one last lonely dude above the ocean in These Final Hours Embrace at Last; This is Our Ending, This is Our Past, O'Neil was ready for something new.

In 2010, she was accepted on the basis of a PowerPoint presentation to study at German director Werner Herzog's "Rogue Film School" in Los Angeles. The experience not only made O'Neil consider the possibility of animating her work, but it also led her to embrace the auteur's "by any means possible" attitude.

"We learned how to pick locks in that class, and how to get through police barricades," she recalls. "The general essence I took from it is, make the work you want to make without thinking about repercussions or perceptions. So many of us get into a horrible dilemma of 'what will people think if I don't make the sweatsuit guys or make a video work?' My ballsy attitude was, I'm going to make what I want to make. I've always felt the right people will find my work."

Ultimately, O'Neil took a chance by collaborating with Irish animator Eoghan Kidney. The result is "We, The Masses," a short featured in the survey that garnered her an Irish Film Board Award. As she loosened up, she was even brave enough to leave her mechanical pencil behind, creating a series of "very loose" oil pastel drawings that were much more raw and expressive than her prior pieces.

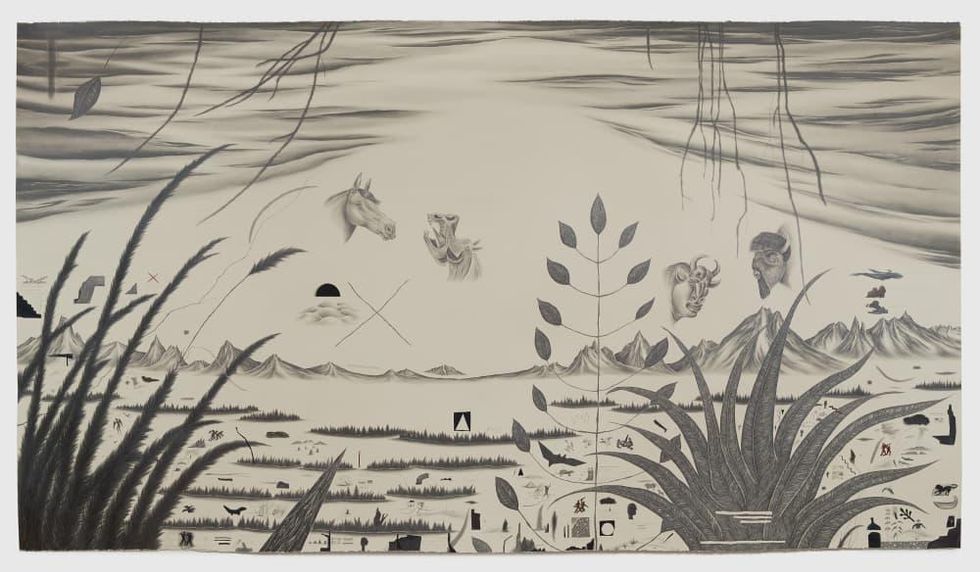

More recently, works like Low American Grace mark another new phase, one in which she references the artists she loves alongside her pop culture obsessions and the weather.

"(Low American Grace) is the very beginning of what will be the rest of my career. I'm finally accepting how many artists I worship. In the older work, it's all Bosch, Bosch, Bosch, Bruegel. But now I'm referencing everything from Oprah Winfrey to Turner. My cloud maker series is me creating storms out of various clouds from history, poetry, and Beverly Hills 90210. I like a lot of lowbrow things more than art and literature. My priorities are the Bravo network and teen dramas."

Whatever direction O'Neil takes, one can be secure in the knowledge that the artist herself is happy with her evolution. A final drawing placed near the exit of the show portrays her tombstone with the wry inscription, "It Could Have Been a Lot Worse."

"I was thinking what a good summary of life (that was)," O'Neil laughs. "It's been bad, it's been good, but it could have been a lot worse. I'm still happy I did all this. If I'm granted another 40 years on the planet, I'm about to get way better. This experience has encouraged me to get to work even harder — I'm dying to get back to it and start again."

---

"Robyn ONeil: We, The Masses" is on view at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth through February 09, 2020.

Robyn O'Neil, As Ye the sinister creep and feign, those once held become those now slain., 2004. Graphite on paper. Overall: 92 1/2 × 166 in.