Movie Review

Anime master Hayao Miyazaki makes return with The Boy and the Heron

Fans of anime have long revered the work of director Hayao Miyazaki, who has made Oscar-winning and -nominated films like Spirited Away, Howl’s Moving Castle, and 2013's The Wind Rises. Miyazaki retired after that last film, and for a long time it seemed as if it would truly be his final film. He found inspiration for another, though, making his comeback with the semi-autobiographical The Boy and the Heron.

The film centers on a young boy named Mahito (Soma Santoki), who when the film opens experiences the tragic loss of his mother in a factory fire. A few years later, his father Shoichi (Takuya Kimura) finds a new wife, Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura), with whom they move to a house in the country. Still grieving his mom, Mahito acts out at school and imagines that a gray heron that hangs out near the house is talking to him.

That fantasy becomes reality one day when the heron (Masaki Suda) leads him into the ruins of a house that belonged to his granduncle (Shohei Hino), where he discovers a magical world filled with strange creatures, like small white blobs called Warawara and human-sized parakeets that talk, as well as a woman named Kiriko (Ko Shibasaki), who shows him the secrets of the world.

(Note: This review is based on a screening of a subtitled version of the film. An English-dubbed version features dialog from actors like Christian Bale, Dave Bautista, Mark Hamill, and Gemma Chan. Both versions are being screened at theaters.)

Most of Miyazaki’s anime contain fantastical stories that serve as allegories for deeper stories. In this film, it’s clear that the death of his mother weighs heavily on Mahito, and the trip into another world is a way of him searching for answers. The parallels between the real and magical worlds are evident, and the pull the magical one exerts, giving him a possible chance to see his mother again, is understandable.

What doesn’t make as much sense is the story told within that magical world. While the imagery is eye-popping and often whimsical – the parakeets alone never fail to amuse – it’s hard to follow the storytelling logic surrounding it. Those who don’t consider themselves anime-philes may find themselves either scratching their heads or completely baffled by what’s presented in the film.

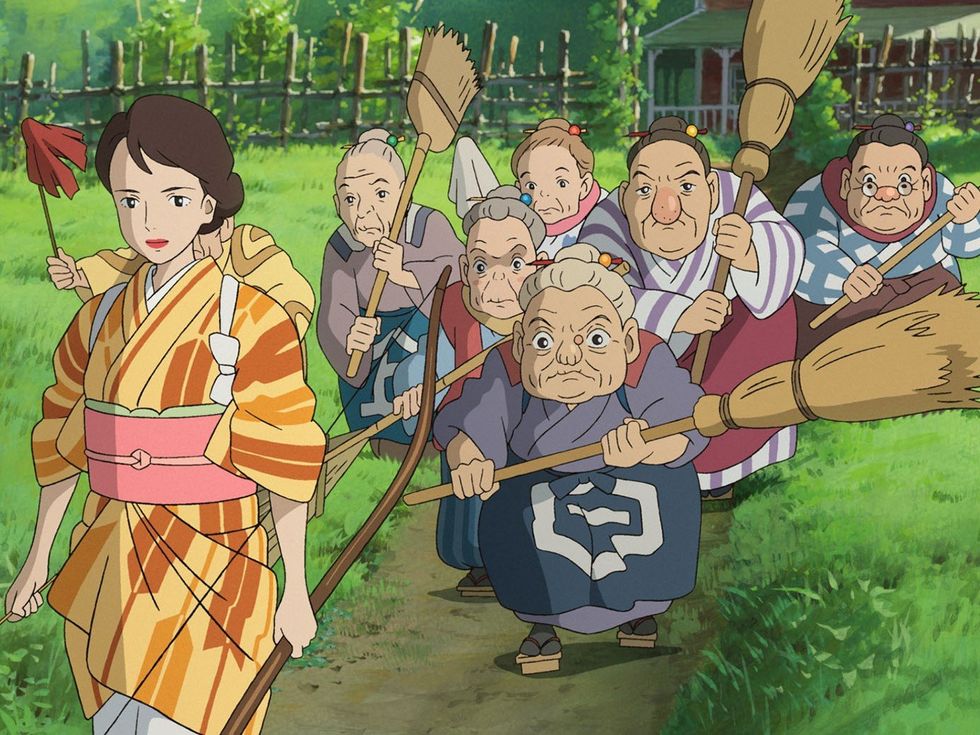

Seasoned viewers will find delight in some of the off-putting characters in the film. Chief among them is the heron, which is revealed to be a man with a bulbous nose inside the bird. The sight of him gradually emerging from the bird’s beak is grotesque and indelible. Similarly, a group of eight elderly women, each of whom are hunched over and have various moles and other odd features, make the film visually interesting at the least.

All of which is to say that one’s enjoyment of the film may depend on how deeply invested you are in Miyasaki and Studio Ghibli films in general. The rhythm is completely different from most American animated films, and so even though it reaches for the emotions that you might find in a Pixar film, getting the requisite release may require viewers to make connections they’re not used to making.

The Boy and the Heron has many of the same hallmarks found in other Miyasaki films, if not as enchanting of a story. There’s no one quite like the iconic Japanese filmmaker, so getting one last (?) film from him is still great even if it doesn’t match his finest work.

---

The Boy and the Heron opens in theaters on December 8.